BECKETT’S ROOM: REVIEWS

Premiere: 23rd September 2019, Gate Theatre Dublin

Chris McCormack

Musings in Intermissions

★★★★★

“Suzanne Dechevaux-Dumesnil, a vigilant member of the French Resistance, arrives at her Paris apartment with alarm. She warns her boyfriend Samuel Beckett that the Gestapo weren’t convinced by her cover story, and that their home might come under attack, in Dead Centre and the Gate Theatre’s extraordinary new play Beckett’s Room.

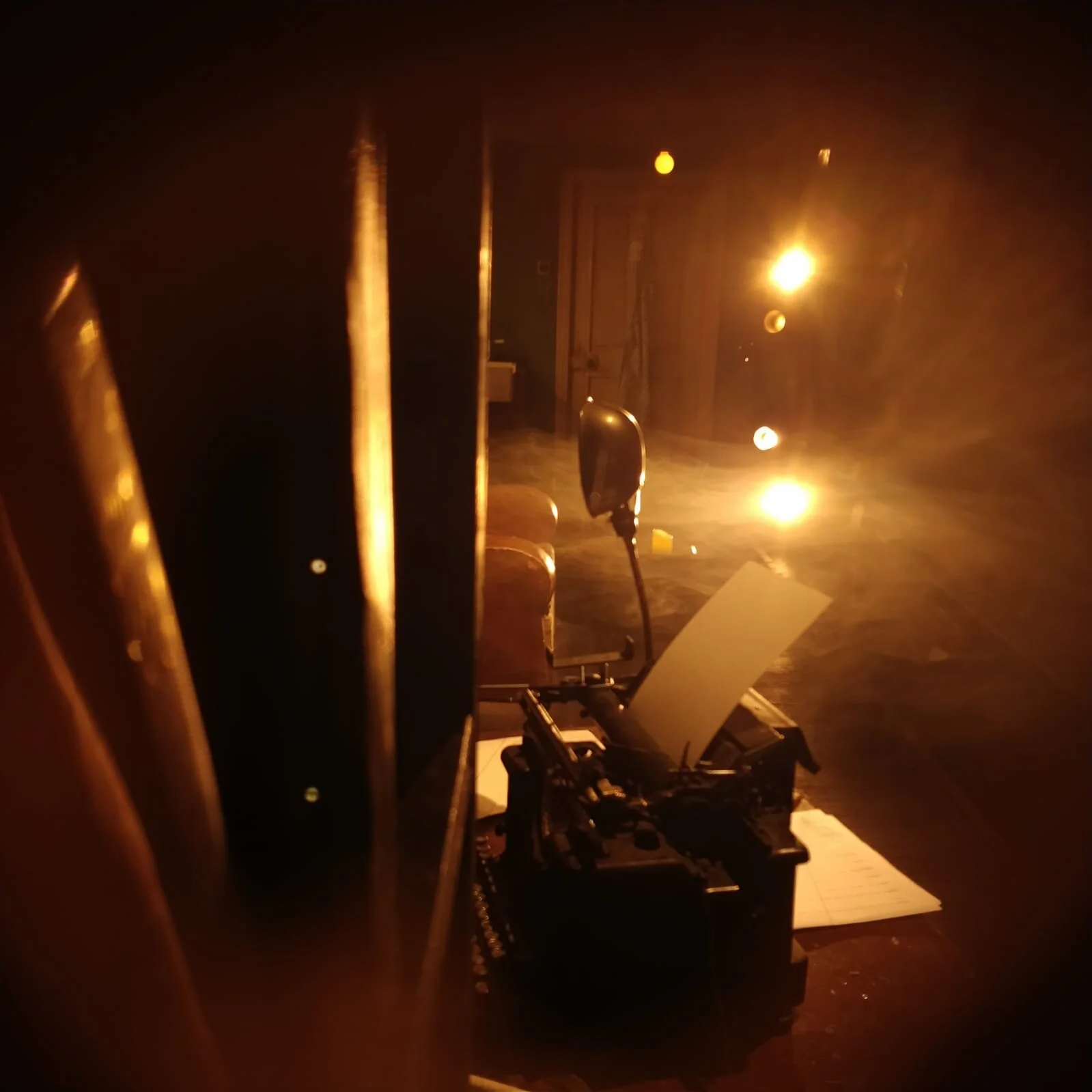

Beckett has yet to become the breakout playwright of Waiting for Godot, but that play's famous no-show inspires how this story is told. Dead Centre’s wonderfully imaginative script, written with Mark O’Halloran, is a play without performers. Suzanne and Samuel come and go in ghostly movements, their presence animated by elaborate puppetry and painstaking lighting. Her coffee cup floats by the kitchen sink, calming her nerves, while his chair swivels playfully behind his desk. Such is the achievement of Bush Moukarzel and Ben Kidd’s miraculous production that both characters are present in their absence.

Through headphones we hear Barbara Probst’s Suzanne, fearful that she will be exposed by the Nazis. Samuel, in the reassuring voice of Brian Gleeson, suggests that they carry on life as normal. They chop vegetables, they kiss. They climb into bed, the sheet levitating magically into the air, ushering them under the covers. For a play without performers, it’s heartwarmingly intimate.

That makes their refuge all the more fragile as the apartment comes under siege. When their landlady Madame Karl (Viviane De Muynck), a Nazi sympathiser, arrives to inspect the home for Resistance secrets, she reflects on her time working in a puppet theatre. “Never looking for meaning, only magic,” she says, describing its artistic vision. For a moment it seems that Beckett’s Room follows the same instruction, delighting with its parlour tricks, until interrupted by Madame Karl's own warped illusion.

More sinister is an invasion by two Gestapo soldiers, who vandalise the apartment and use it to torture a prisoner. One solider, a new recruit clueless about his mission, is quizzed about his knowledge of Mein Kampf, before his senior officer sets a copy on fire. War seems like a theatre of the absurd.

Stained with the memory of blood, the apartment mightn't be able to be a home. But there, sitting in the dark without electricity, friends are reunited and tell stories of gathering somewhere else: the theatre. As Suzanne’s experiences of the war are built into an unsettling metaphor - a Paris of disappearing bodies, powerfully depicted by José Miguel Jiménez’s video projection - it seems like they could be the source of Samuel Beckett’s storytelling.

That’s an intriguing idea, but the play’s strength lies in its touching tale of survival. At one point, Samuel turns to Suzanne as if it were a fresh realisation. “Now I see you,” he says. No one else can see them, in their own private void, away from a world at war.”

Link here

Emer O’Kelly

Independent on Sunday

“Did Beckett run from the void, or into it? Beckett's Room asks the question. Beckett merely showed us the void without comment. But what this extraordinary play without actors does is to give us a visualisation of the nothingness at the centre of Beckett's work: a nothingness that bursts its own seams with anguish and with the echoing sound of silent howling.

Devised and written by Dead Centre (Bush Mouzarkel and Ben Kidd) and Mark O'Halloran, and directed by the first two, it's set in the Paris flat that Beckett shared with his lover Suzanne Descheveaux-Dumesnil from 1937 until 1960.

Except for the years between 1942 and 1945, during which the couple, members of a betrayed resistance cell called, ironically, Gloria, fled south to Roussillon where they continued their resistance work as best they could. The flat was left to echo the howling of a humanity in the process of destruction as Paris fell, and Nazism seemed to be the irresistible future. Except. Except for the individual, who, Beckett was to find in his writing, was the conundrum. The individual can either face the darkness and survive, or turn from it and be destroyed.

Beckett's Room, empty other than when being invaded by the Gestapo who may well use it, desultorily, as a torture chamber, survives on the echoes of its residents' voices, fearful, unsure, desperate, but still human.

It's an extraordinary piece, given a quiveringly terrifying life through the voices of Brian Gleeson and Barbara Probst as Beckett and Suzanne, and an equally, drainingly wonderful support cast of the voices that peopled and shadowed their lives in the years that formed Beckett's genius. Technically, it's superb; intellectually, it's devastating; emotionally it's searing.”

Link here

Peter Crawley

Irish Times

★★★★

“There’s no better audience than young people, enthuses a sinister visitor to Samuel Beckett’s apartment in Nazi-occupied Paris in 1942: “Never looking for meaning, only magic.”

In Dead Centre’s wildly ambitious co-production with the Gate Theatre, on the other hand, there is meaning in its magic, depicting this furtive and formative time in the writer’s life as an elaborately conceived disappearing act. We do not see a cavalier Sam and his much warier partner, Suzanne Dechevaux-Dumesnil, on Andrew Clancy’s two-tiered set, but we hear their voices and observe their trace. Beckett’s chair swivels as he types out coded messages for the Resistance. Suzanne’s body, and even her breathing, leave impressions on a battered sofa. Like Godot, they are conspicuous by their absence.

To an audience of young and not so young people, this initially carries the goofy pleasures of a dazzling parlour trick. Listening to Brian Gleeson and Barbara Probst’s voices on headphones – moving through the space, in Kevin Gleeson’s fastidious sound design, as pronouncedly as Foley footsteps – the effect is of an illustrated radio play; albeit, in co-directors Bush Moukarzel and Ben Kidd’s collaborative script with Mark O’Halloran, more narratively conventional than anything Beckett would have created.

Beckett’s Room: The voices of Barbara Probst and Brian Gleeson can be heard through headphones

As subtitles track across the scrim, translating Viviane De Muynck’s landlady and collaborator as she snoops (at one wickedly amusing point, controlling her own marionette witch), and later trailing Gestapo members as they ransack the deserted home, your attention is ushered from place to place. Sometimes you see the reflection of a person, or, more effectively, their shadow, while your imagination fills in the gaps.

Anything less than perfection in these stage effects tends to break the spell and, impressive as the puppetry is, the effects are not perfect. Floating objects can becomes complicated to the point of entanglement; plumes of cigarette smoke clever to the point of distraction. The text, likewise, bears many fillips, lightly alluding to its own conceit (“No one can see us”) while imagining the cruel absurdities of the war as prefiguring Beckett’s Godot: a carrot and turnip supper, the stasis of war (“Let’s go,” says one German soldier, during a menacing double act. “We can’t,” says his superior), a voiceless, tortured “pig” prisoner, Suzanne’s recollection of their vagabond existence.

If that asks you to see Beckett’s life in his work, the play finally becomes more thesis than biography. In one interlude, José Miguel Jiménez’s excellent video work erases figures from Paris’s streets, before Beckett’s artists friends admit to never seeing a body during the war. Yet they must recognise them. And what is more difficult, after such horrors have changed the world, they must find new ways to represent them. That is where Dead Centre make meaning from their magic, with an outline of how Beckett came to depict the unimaginable, if we’re willing to see it.”

Link here

BECKETT’S ROOM was produced in co-production with the Gate Theatre, and presented as part of Dublin Theatre Festival.

Co-commissioned by Irish Arts Center and Warwick Arts Centre. Development supported by Trinity Creative Challenge and the National Theatre Studio

Supported by the Goethe Institute and Dublin City Council. Supported by the Arts Council

For touring information, please contact info@deadcentre.org